Nietszche recommended a genealogy of morals that was rooted in the psychosocial. There used to be just the strong and the weak, he argued—those who reached, experienced, and took great strides in the world, versus those who retreated, shrank back, and were fearful. The former were life-affirming; the latter negated life by refusing to fully engage in it. Eventually, resentment was born in the weak because when the strong took steps in the world, they intruded on world of the weak. The eagles ate the young lambs. And so, the weak, the sheep, eventually invented the word “evil” and assigned it to those displaying characteristics of strength and nobility, and then reflexively called themselves good. Blessed were the meek, the mild. Cursed were the proud, the merry or the wild (the ones that could not be corralled by duty or social constraints). And so morality was born out of bitterness, out of a profound pettiness. And it operates to harness greatness of spirit, to turn will against itself through conscience, to domesticate the nobility of being. It is the circus bear. It is the lion that performs tricks. That is what morality has done to us, this ideology of the weak.

I love the cleverness of this idea, but I don’t agree with it. Here is another approach:

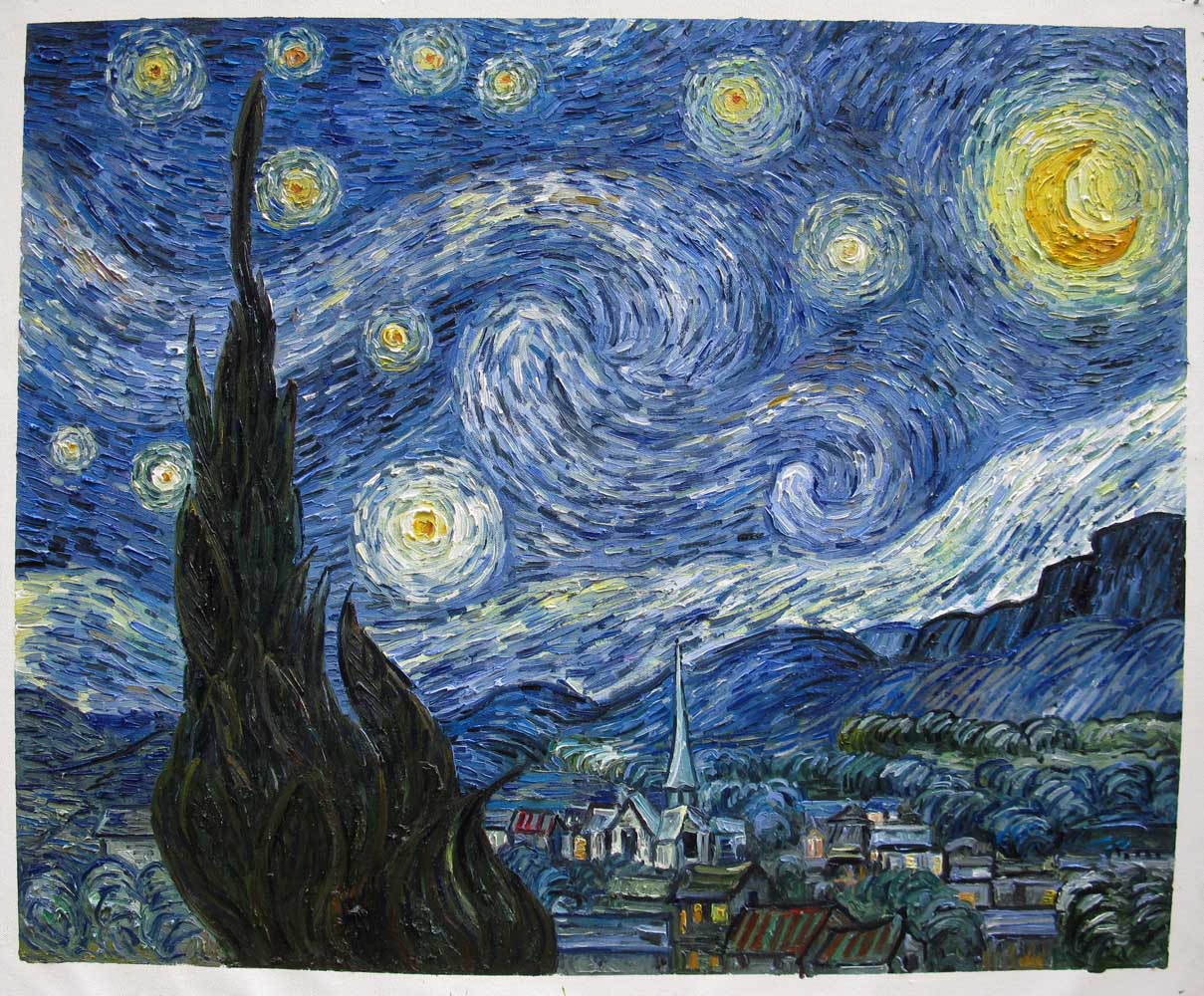

I am told that some ancient cultures believed that at night the gods threw a blanket over the earth and the stars were pinpricks behind which heaven could be glimpsed. Today, we believe the stars are isolated balls of burning gas. As such, they are not portals of heaven. They do not represent the continuity of the eternal, the transcendent.

Consider the moments of experience to be like stars within these different paradigms. There are two ways we can think of them, either as singular events (an aesthetic lens) or expressions of the transcendent (a moral lens).

Suppose I experience a moment of love, or joy, or hope. The moral view cannot contemplate these as singular, isolated events, but only as linked to axioms that transcend our experience. They are expressions of the universal. They are temporal manifestations of eternal principles. They exist in our experience only because there is an enduring foundation that supports them.

The accent falls on the heavens, then, not upon the pinpricks of light. We can accept the passing nature of meaning in such moments because we believe they continue to abide beyond our experience of them.

We believe, too, that we can invoke them through dogma and duty. We invent obligation, commitment, promise, and duty because the transcendent is the guarantor, not the moments. In this way we aspire to manufacture a continuity of moments, to shrink the emptiness between them. Our gaze encompasses the something behind the moment, the something better, something truer, something deeper.

Now we are gods, with power over the universal, over heaven. By performing our duty, by complying with the rules, by invoking and imposing dogma, we either (1) sustain the form of love (or whatever value) in the darkness between our experiences, or (2) we summon it from its glory and are washed anew in its light.

The good and sublime underwrite our experiences, assuring us there is a world of meaning even when it doesn’t erupt in subsequent moments. Even in the darkness between such moments. And so we can create social institutions and mandate them to last, just as love lasts. We make promises and ask for promises because moral duty requires continuity, just as the heaven after which they are fashioned has continuity.

Meaning. Purpose. Love—isolated stars cannot sustain these things, but heaven can.

Right?

Or…

Moral imperatives are the imprints left of meaning, the derivatives of meaning, not the heralds of it. They are the smoke, not the fire. What burns bright and hot is not the eternal but the sheer beauty of the fleeting. The fragile. The temporary. They do not reflect some universal “thing” etched in the invisible foundations of experience.

Instead, the journey into infinitude is not a horizontal one, but a vertical one. It is about plumbing the impossible depths of moments. It is indwelling this “now” and submerging oneself in its winter or its summer. Each moment implies a universe, a past and a future, our no longer being possible. Each moment is suffused with beauty before cascading into oblivion, into forgetfulness. This is the narrative of our lives, and it is impossibly deep and inexpressibly beautiful.

Moral imperatives, on the other hand, are the engineered scaffolds upon which we hang our longing. Too often they require contortions of spirit, demanding that we comport ourselves to that which cannot be experienced. We must supplant immanence with transcendence, the transient with the eternal, and see ourselves in the mirrors of perfection.

Of this particular beauty or that, there is only contempt, for no particular beauty remains. And if all things fade, how can it birth meaning?

Precisely, I think, because it fades.